ZAH is a new jazz group pursuing a specific goal: the complete three hundred sixty degree expression of modern musical sensibility. It is a music tending toward a larger articulation, drawing on the unlimited resources of tradition as well as sudden, raw inspiration. All creative elements are carefully shaped, or left unshaped, with the expressive ideal in mind. Saxophone, bass and percussion are the components; they combine in a straight-forward way, producing an uncluttered environment in which each instrument is featured with chamber-music clarity. If it serves it’s purpose, ZAH will meld Buddhist cantillation with insane fortissimo ring-modulated clusters, post-Coltrane sax lines with Neolithic ritual, florid Classical cadenzas with crippled disco rhythms. And, of course, them blues, them changes. ZAH is a continually evolving music concerned with growth, not market-place expediency.

Jazz Echo, Publication of the International Jazz Federation, Inc Vol. 9, no. 42 October 1979

In 1979 saxophonist Mel Ellison, bassist Michael Willens and percussionist Michael Levenson went into Downtown Sound recording studio in New York City to create an album of music under the band name ZAH. It was never released. The studio went out of business a year later and the master tapes are almost certainly lost. It’s not the first such story in the music business but it’s one that crosses my own trajectory albeit tangentially.

I wrote about Mel Ellison ten years ago in the second post of this blog. Mel and I met in 1979 when he was playing with trumpeter Ted Curson in my hometown of Baltimore at a club called the Bandstand. The owner of the club, Mike Binsky, had produced a three day festival presenting a host of musicians including Sonny Stitt and Ted Curson. During the afternoons there was a jam session with the rhythm section of Ted Curson’s group, pianist Armen Donelian, bassist Ratzo Harris and drummer Tom Rainey. I came by to play and got my first lesson in New York attitude from Armen when he rolled his eyes at the fact that I couldn’t play the tune I had called in the proper key, asking him to transpose. But things went well enough and I had a chance to talk with each of them about New York. Sonny Stitt came in that afternoon and saxophonist David Schnitter was hanging with him, almost literally. Everywhere Sonny went David was right there asking a question, “Sonny, what about this? Sonny, what about that”? Sonny couldn’t move his arm without David trying to get a little closer, to see what Sonny was doing. It was a beautiful thing to see David’s admiration for Sonny, trying to pick up anything he could for the music. The photograph posted here was part of Mike Binsky’s promotional effort, driving Sonny Stitt and company around the city in a convertible limo with the festival poster (where you can see the Ted Curson Sextet listed) draped prominently on the side. Sonny Stitt is in the back seat and David Schnitter is seated next to him. In the front is the late great Baltimore saxophonist Arnold Sterling.

In addition to the aforementioned rhythm section was Mel Ellison on saxophones and Montego Joe on percussion. Ted Curson had once played in bassist Charles Mingus’s group and the energy crackled in much the same way. The music swirled in a million directions but my attention was largely on Mel, playing like I’d never quite heard anyone play the horn before. A very dark sound with all kinds of oblique intervals. I went back again the second night and asked Mel for a saxophone lesson. We met the next morning and I had a chance to speak with him at length during the half hour drive each way through city traffic from his hotel to my place. I was nineteen and my head was in the clouds as I became increasingly engrossed in the conversation only to have Mel calmly inform me that we were stopped behind a parked car. I don’t quite remember everything that took place in the lesson but there was a good amount of tried and true advice given around issues of musicality. The main thing was his vibe, the way he spoke and handled himself. He was gentle and caring, even somewhat self effacing. At the same time it was like,

you knew he knew. It wasn’t so much what he said but you just felt it.

One weekend about a month later I decided to take the train to NYC for a visit to see for myself what it was all about. I didn’t know one borough from another, had no place lined up to stay and didn’t know anyone in the city except Mel, whose number I had with me. I figured I’d take my horn, a little cash, find a cheap hotel for a couple of nights and just look around. The train conductor announced New York City and everyone disembarked, slowly working their way upstairs. I was hungry so I ordered something at the station deli, took it to go and was immediately overwhelmed upon hitting the street. People were MOVING, endless lines of folks all winding their way around each other. I just wanted to eat and there was nowhere to be so I found a piece of wall to lean up against and grab a few bites. Within seconds an enormous guy smiling a big huge grin come right up to me and demanded

“Gimme your sandwich!” I moved and kept moving for blocks, looking for a suitable hotel, finding everything to be way over the money I had. Eventually I found myself in midtown and saw a sign for the Fulton Hotel. Rooms were only $12 bucks a night. Relieved I walked up the stairs and encountered a man sitting behind a plexiglass barrier, the manager I assumed. The place was old, dark and dank, the wood floors creaky. There was a sign that ran down the cost of the rooms. Hourly rates were also available. The clientele seemed furtive, nobody smiled, hardly anything was said. I paid for a night, went to the room, looked out the window and stared for a long time. Innumerable yellow taxi cabs lined the avenue.

I took out the piece of paper with Mel’s number on it, went to the payphone and dialed having no idea if he was in town or not. Mel picked up and I announced myself as the guy who took a lesson a month or so back. “Sounds like someone’s in the Big Apple” he said. After a brief conversation Mel invited me over to his place. “I’m just a few blocks from your suite at the Fulton” he said. Mel lived on West 46th street in a walkup. One room is all I remember and a pretty spartan one at that. There was nothing except a bed, a television set, a stereo and a huge cappuccino maker, the kind you might see in an Italian restaurant. Mel had his horns out and was practicing. Standing in the middle of the room with his saxophone, bare floors and walls, minimal accoutrements, combined with his calm presence he gave off a monk-like aura. Maybe it was his Bay Area roots, but he was rather laid back, not at all anxious or up tight about things but at the same time I could tell that he took it all seriously, just not too seriously.

As he was playing I became so inspired that I decided to take my horn out, unasked, and tried playing with him. This was much more forward than I would be in any other situation and I couldn't believe I was actually doing this but it felt almost magical, as if these were the best notes I'd ever played before. Mel stopped playing and didn't say anything. I was a bit uncertain as to why he didn't acknowledge my playing but at the same time it was all cool, he wasn't ruffled nor did he convey any kind of attitude. We kept talking and at a certain point he decided to play some music he’d recently recorded. All I remember was that I liked it but couldn’t really say what it sounded like, it was elusive to my ears, I couldn’t grab it. In retrospect I’m pretty certain this was a recording by a group he was in called ZAH. Mel said "I've played every kind of music and gig there is and at this point I only want to play the music that I want to do”. I could tell that this was not a selfish statement given that he backed it up by driving a taxi and later a limousine to make ends meet. He's certainly not the first person with such a story but he was the first such person that I had met and he lived in NYC, the place I wanted to be, intimidating as it was especially at that time. All in all he was enjoyable to hang out with, laughed easily and had a positive vibe even as he did not shy away from the urban realities he was immersed in. After all, this was Times Square in the ‘70s, not at all a playground.

I tagged along, riding the subway with him and one of the trombone players who struck me as tremendously underdressed for the occasion, raggedy jeans, sneakers and a rumply t-shirt. He didn’t look like he was on the way to a gig at all, more like he’d just got up out of bed.

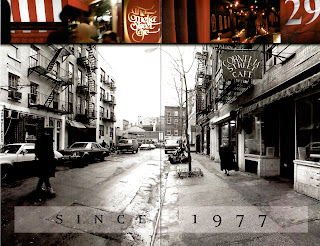

Everyone struck me as being pretty relaxed about everything.The gig took place at a loft space downtown called Ali’s Alley, drummer Rashid Ali’s club. There were tables, the place was fairly full and the band set up against the wall. My first reaction was that the music was loose, very loose. It almost sounded like a rehearsal in some ways although there was spirit in the soloing. It all seemed a bit odd and perhaps combined with the fact that I was finally sitting down everything seemed to hit me all at once and I began feeling very uncomfortable. The feeling built until I began to get worried that I wasn’t going to be OK. I needed to move, I needed not to be where I was but there was nowhere to go. I got up anyway, walked around the back and saw a curtain behind which was a small room. It looked like it may have been someone’s living space but no one was there so I laid down on the floor and curled up. The band continued playing for awhile and then took a break. I was still kind of freaked so I remained there hoping no one would come in and say anything. After about five minutes the curtain opens up and Jaki sticks his head in asking “Is this your room”? I don’t know what I might have said but he was completely cool about it and left. That kind of jolted me back to getting my shit together and I got up and walked back out feeling a little better. This would seem to fit the description of a panic attack, something I knew nothing about. The saving grace was that relaxed, laissez faire attitude that everyone seemed to have. It was all cool, do what you need to do, nobody cared! I think I let go of a lot that evening, for the better.

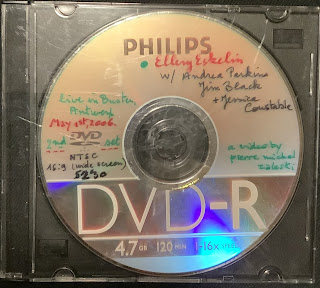

By the time I’d moved to NYC in 1983 Mel had left town and relocated to the Bay Area where he was originally from, having left the music business entirely I was to discover. Before the internet it was not so easy tracking folks down but by 1998 I managed to connect with Mel on a visit to the Bay Area for a gig I was doing with Andrea Parkins and Jim Black at New Langton Arts in San Fransisco. Mel came to the gig and we had a chance to chat a bit afterwards. Mel mentioned that certain things he heard us doing reminded him of what ZAH was doing back in the day. It wasn’t until 2010 that we met again, this time in NYC on a visit Mel made with his wife. I organized a session with bassist Ratzo Harris and drummer Tom Rainey, Mel’s bandmates in the Ted Curson band. They hadn’t seen each other since. It felt great to bring that experience full circle. Mel sounded wonderful.

We’ve continued to stay in touch and at numerous times along the years I’d remind Mel of that elusive music that he played me at his apartment in 1979. I really wanted to know who and what it was, I just knew it had never been released commercially. The mystery remained and I assumed I would never know. To my surprise I got a package in the mail some months later from Mel with several cassettes, one of which was the ZAH recording session. I didn’t know it at the time but it was his only copy. It was a thrill to receive this and while I was able to parse things out better than when I first heard it, it retained it’s unique sound. I was surprised that I had not heard of the other musicians. Mel didn’t know what had happened to them after he left NYC and I eventually filed the cassette along with the many other tapes I’ve amassed over the years, some number approaching four hundred, going back to 1974.

Some months ago I began the process of digitizing all of them. I posted about that project here. In coming across the ZAH tape I was struck all over again by the music. I still don’t know quite what to say about it. I brought this up to Mel and began pestering him all over again about the music and any recollections he might have from that time. At a certain point I asked “have you done any formal interviews in which this has all been laid out? If not, I think that should happen.” Mel replied “We were invited to do an interview on a well-known, at the time, NYC jazz radio station just before a gig back around 1981 or so. The other guys did the interview while I and my, at the time girlfriend, sorta walked around the studio. For some reason I didn’t want to participate. Otherwise I haven’t done any formal interviews about this, I’m not sure anyone cares really!” I told Mel, “I care! And I know there are many folks out there who also care about this music and it’s history.” And with that I realized I had just signed up for the job. I also wanted to get a better sounding copy of the recording since my cassette was not all that great and my transfer was questionable at best, it needed a professional job. I was already in the process of discarding tapes that had been transferred and catalogued when Mel said he didn’t think he had a copy any longer. My heart nearly stopped. Did I just throw away the last remaining copy of this music?

At this point a search began in earnest. Mel managed to locate bassist Michael Willens. Turns out Michael left the city in 1996 and relocated to Cologne, Germany where he is the founder and director of

Die Kölner Akademie, a period instrument orchestra and choir. Michael didn’t think he had a copy either but he did remember the name of the producer of the session, Chris Whent. Chris had produced many sessions for Polydor, was a lawyer and also hosted a music program on WBAI radio. I managed to get Chris on the phone and while he remembered the session he was pretty adamant that the tapes were lost when the studio went out of business in 1980. For reasons still unclear the session was never released. He mentioned the name of the studio as Downtown Sound and with that I was able to find the name of the studio owner, Hank O'Neal, and got him on the phone. Hank seemed to enjoy these kinds of calls and before long was regaling me with stories from back in the day. When the studio went out of business he put out a call to everyone who still had tapes stored there to come and get them. When the final day arrived there were still some tapes left behind and he wasn’t entirely sure what happened to them. They may have found their way to Williamsburg for storage but that lasted only a couple of years and after that the trail ends. The chances are slim we’ll ever locate them but it’s been good to follow this out and put at least part of this story to rest. At the same time, I was beginning to despair that this music would never see the light of day. So I made one more push with Mel and Michael to give another go at searching their archives. After a few days Michael got back to us and said “we’re in luck!”. He had located some files that he had once made of his copy of the recording and they sounded much better than what I had. I convinced Mel and Michael that this music deserved to be heard and offered to present it here on my blog. Engineer Jon Rosenberg did fantastic work in cleaning it up and both Mel and Michael were thrilled with the results.

My original intention was to simply interview Mel and post a transcript but he seemed to feel that Michael Willens would be best able to answer my questions about ZAH as he was more the impetus of the group’s formation.

Michael’s first statement was “that whole period is kind of a blank for me at this point” so I wasn’t sure we were going to get very far but as we proceeded things began to fall into place.

Michael described the group as being a synthesis as far as his playing experiences (which were quite varied) and his listening to groups like Circle (with Chick Corea and Anthony Braxton), Cecil Taylor, and Charlie Haden with Ornette Coleman. One of the distinguishing features of ZAH was it’s instrumentation. Percussionist Michael Levenson played an array of mallet instruments including vibraphone, marimba and glockenspiel as well as cymbals and various other instruments. On the recording he would often play in time on a cymbal with his right hand while playing chords on the vibes with his left. Additionally he employed a ring modulator on the vibraphone creating some other-worldly sonic effects. It often sounds like more than one person but the recording was done all live.

Michael Willens: “We played a lot together, each of us contributed some music and we worked on these tunes, each of us had a concept of a piece and we would play it and play it and play it until it came together the way we felt it was saying what we wanted to say. The chemistry worked, like chamber music. It’s what everybody does, it’s not unusual but it brought us to a different space.” I pointed out that there was some screaming at a certain point on the recording. “It was very cathartic that particular track. The music still speaks today, it’s out of an era but it still has validity”.

The third member of ZAH, percussionist Michael Levenson, has proven to be the most elusive. As with bassist Michael Willens, Michael Levenson was involved in the contemporary classical music scene in NYC. This is an interesting aspect of the story given that in the ‘70s there was not yet the full confluence or exchange between musical traditions that we might take for granted as existing now. It seems that both Michael Willens (who graduated from Juilliard), and Michael Levenson (who graduated from Mannes School of Music) were fortunate in finding themselves at a musical nexus that has blossomed since then. Their work, along with Mel Ellison, foreshadowed much of what has come afterward. In any event, I could only trace Michael Levenson’s activities up until the early eighties and then he seemed to have dropped off the radar. There was one interesting citation appearing in the Village Voice written by Tom Johnson in 1972 as part of a larger review of performances taking place at The Kitchen when it was located at the Broadway Central Hotel.

October 19, 1972

Opening the Kitchen Season: Laurie Spiegel, Jim Burton, Judy Sherman, Garrett List

Michael Levenson’s “Coke on the Rocks” begins as a militant snare drum solo. Then he pours lighter fluid over a large, economy-size Coke bottle and sets it on fire. As the bottle burns, he returns to his snare drum and plays jazz riffs with brushes. His excellent drumming sustains the short piece well, and the simple stark image of the burning Coke bottle, in context with the drumming, makes an arresting statement.

Levenson’s other theatre piece, “Professor Throwback Presents”, conveys much less through much more. Wearing a gorilla mask, he burns classical sheet music, does a bad magic act, induces a member of the audience to suck her thumb, draws meaningless symbols, etc., etc. It is more or less impossible to relate the many events, and the piece as a whole is pretty confused.

Both Mel and Michael had fond memories of their friend and his sometimes off the wall comments. One time Mel suggested to the guys “maybe we should dress up like Art Ensemble and wear some kind of costumes”. Levenson fired back, “what are you gonna do, dress as a surfer?” I was intrigued but prepared to think I’d never locate him as my searches were going nowhere. But then one evening a rather obvious clue came to mind that I had overlooked and shortly before my self-imposed deadline for this post we made contact. In an e-mail exchange he graciously answered a dozen questions, his brief but witty responses matching his bandmates recollections of his personality. And before I mislead anyone about the aforementioned anecdote, here is what he told me about his former bandmate: “I had great respect for Mr. Ellison as a human being and as a jazz saxophone player.”

A few other comments from Michael Levenson…

On his choice of ZAH as a band-name:“ZAH comes from the dictionary although you will not find it in every dictionary. It is a prefix to other words and it is used as an intensifier.”

On his composition titles:

“‘What You Need to Hear’ is a lighthearted take on the voice of a father talking no nonsense to his child. ‘Christmas 1954’ is based upon a photograph taken at Christmas of me at age 3. ’10:30 on the 11th’ is a sardonic comment on the timelines of modern life. ‘Park Avenue Mothers’ derives from watching a beautiful, wealthy woman on upper Park Avenue walking her infant child in a baby stroller.”

On playing multiple instruments at the same time:

“I did play multiple and this was managed through very exact placement of the instruments, along with knowledge of my personal foibles.”

On his electronic effects:

“The modulator was an add-on accessory which plugged into the amplifier bar on the vibraphone. Vibraphone amplifiers were not widely used. They consisted of 2 long bars, each bar attaching to the horizontal support, front and back, which held the metal "keys" of the vibraphone, and were output to a small guitar amplifier.”

On being asked about his feelings on the music:

“The only thing I would say is that my intention was to demonstrate the stunning variety and depth that could be achieved with talented people utilizing minimal resources and available technology.”

On later activities:

“After emerging from graduate school in 1983 I left the music industry permanently.”

Anything else?

“You deserve a medal. Or at least a dry crust of bread.”

This all brings us back to Mel. I've since spoken to a few other folks who knew Mel from that time and they all convey a deep respect for his artistry and dedication as well as an admiration for him as a person. Apparently Mel was considered the new young rebel in San Fransisco during the mid seventies and had already achieved legendary status in the circle of musicians who were aware of him. Tom Alexander (founder of

Alexander Reeds International) was a young saxophonist in the Bay Area at that time. When I told him I was working on this article he said “Fantastic that you're writing something about Mel, a true original, under-appreciated and brilliant. Man, Mel was baaaaad, we young saxophone players couldn't believe it, we never heard anyone play like him. He graciously took me under his wing and helped me immensely. He was such a great cat to learn from and not just about saxophone playing. I have never heard anybody then or later play with the same approach he used, it was quite unique from his tone to his execution to his ideas. A very spiritual cat and it came out in his playing and just talking with him.”

Two other musicians who knew Mel well were bassist Michael Formanek and drummer Tom Rainey. Michael Formanek knew Mel from the Bay Area before moving to NYC himself in the summer of 1978. Mike was staying with saxophonist Dave Liebman when he contacted Mel by phone. Mel was living on Delancey street, at the foot of the Williamsburg bridge and helped Mike get his own apartment in the building. In telling Dave that he’d found his own place in that neighborhood Dave said “You’re going to have to get a gun!”. When Mike demurred on that idea Dave simply said “well then make sure you look mad whenever you’re going in and out of that place”. Mel later moved to midtown and Mike recalls many jam sessions there. “Mel straddled the line between open/free and tunes/structure, a magnificent change player and great free player. He played all the time when he wasn’t driving. Super peaceful, he would have an espresso and zone into the music, a kind of stream of consciousness. I always felt a strong inner drive, a bit of aggressive energy underneath but his demeanor was like breathing, not forced, naturally but with a strong edge to it.” When I asked Mike about Mel’s spiritual vibe Mike said Mel was like a Zen master in which it’s all very practical, no hero worship involved at all. Mike summed it up well by saying “it’s hard to put your finger on it because it’s real”, to which I concur.

I followed up with Tom Rainey on that theme and he agreed, remarking on the power and intensity of Mel’s playing, the likes of which Tom had never experienced before. “Mel was the first guy I really improvised with, we would just go! The feeling was so strong. Twice in my life I’ve had the experience of levitating when playing. Once with Mel and once with guitarist Bill DeArango. I felt I was literally lifted off the ground while sitting at the drums.“ Tom lived for a time in Long Island City and organized regular sessions with a group including Mel, bassist Ratzo Harris, guitarist Bill Frisell and flutist Norma LaTuchie “The sessions served as a release and became almost theatrical at times. The feeling was that there were no gigs, there was no dream of a gig.”

Asking Mel questions over the years has been interesting. He would say things like “Music was more therapy for me if anything. I always felt like there had to be an area in one's life that was untouched by the forces of the market place, so to speak, something that is done just for the sheer fun of it. In my case it was my music. I often felt compelled to make it work economically and it never seemed to happen, the quality suffered and I wasn't enjoying it.”

His brevity belies a deeper, unspoken understanding of things and maybe that’s part of why I’ve continued to press him on certain points. I should say he has always been open and done his best to accommodate me. I recently asked Mel about his influences.

“As far as how I arrived at my approach it’s a little harder to put into words. When I won a scholarship from Downbeat Magazine to Berklee School of Music in 1965 I, like many other white boys, just wanted to play bebop. I eventually got sick of it and quit music for a time. When I picked my horn up again around 1969-ish I had been reading J. Krishnamurti extensively and meditating a lot. I decided to play only what sounded good to me, and instead of fighting the horn to overcome it I tried to let the sax tell me what works best. I explored and pushed the limits more and more, always playing rhythmically and only what really sounded good to ME and what seemed to lay well on the horn. Instead of approaching the sax as a problem to overcome it became my friend and collaborator, we worked together. There is more to it, especially when I decided to quit again and why. I will say it’s the same approach I now take with the piano and I’m loving it!”

That’s a great answer but I was intrigued by something Tom Rainey told me about a conversation many years ago with Mel about John Coltrane. Tom was surprised when Mel said “Everybody talks about Coltrane but I think Sonny Rollins is the cat”. I asked Mel about this and he confirmed saying “God, I love Sonny Rollins! Coltrane was a singular voice but when Sonny plays it’s a history of everything that’s ever been done on a saxophone”.

On leaving the music business:

“Funny, that whole period of time is frozen in my memory, like those photos. I completely turned my back on it and went another way as you know. The reasons were complex and not fully understood by me at the time, if even now. There was an inevitability to it, a sort of a death if you will. In a nutshell, I wanted to see if I could 'be' without being ‘Mel the jazz sax player’, or ‘Mel the anything else’ for that matter. It was, and is, a very humbling yet edifying experience. I've been fortunate to have met some wonderful people (and some not so wonderful people) along the way. People who I would not have met nor would have learned so much from had I continued the way I was going. I still have to wonder sometimes what might have been. I think I was a lot closer to breaking through than I thought at the time. Thomas Edison is quoted as saying: ‘Most people who are failures in life have no idea how close they came to success’. In one perspective I was a failure: I didn't live up to my musical potential. But ultimately, the universe will be the judge of that. One of my early saxophone heroes, Flip Philips, said once: ‘When it stops being fun, I'll quit’. That always stuck with me. I loved the playing and the exploring part of the music. It was the political, social and cultural part that I found difficult, nor was I very good at it even if I wanted to be.“

Tom Rainey has spoken to me of Mel’s “calm containment” from which emerged a “laser focus”. We both felt this quality to be similar to John Coltrane and Mel has certainly absorbed much of Coltrane’s approach. But Mel doesn’t sound like Coltrane, he sounds like Mel. And so I finally asked Mel point-blank about intensity.

“It comes from confidence. I don’t care if people like it or not, I play what sounds good to me. It’s a feeling that I’m good, I can do this. Not in an ego way, trying to put something over, just, I got this. I mean it and that’s all there is to it.” I hadn’t heard Mel speak this way before and so we continued in this vein on intensity until he offered “I think it emerges out of deep, dark sadness. It’s a sad world although we try to be happy. A saxophone is your heart and soul, a voice.” Relating back to influences he cited Charlie Parker. “His tone went right to my heart, there was a sadness and a poignancy.”

That resonates quite strongly with me and I think it’s something all musicians feel even as it’s addressed in countless different ways. Perhaps one of the most concise ways of putting all of this came from Kathryn King who was acting as the PR representative for ZAH in 1979. She has been active in the music business ever since, creating her own company, Kathryn King Media. Upon reaching her by phone she said “You could have knocked me over with a feather when I received your e-mail!” She also recalled a number of details that were missing including the fact that the album was to be titled after one of it’s tunes, “10:30 on the 11th”. But it was this comment that I think says it best:

"Mel was a man of few words but what came out of his horn was an explosion of feeling.”

post script:

I want to express my deep appreciation to Mel Ellison, Michael Willens and Michael Levenson for their music and for allowing me to tell something of it’s story. Thank you gentlemen.

Since his departure from the music scene Mel has followed a passion for sailing and photography. You can get a sense of his many seafaring journeys on his website, Mel Ellison Photography.

Listen:

This is the music of ZAH. We’ve done our best to restore what was an old analogue recording that was digitized at an unknown time under less than certain circumstances, now given a twenty-first century digital clean up. Some of the musical electronic effects used during the original recording may not strike your ears with the same kind of pristine sound we’re used to today but it’s not at all difficult to immerse yourself and surrender to the sounds. With a good set of speakers and about forty minutes of uninterrupted time this music will do wonders for one’s soul.